Chapter 4: Introducing Rhetorical Analysis

In this chapter, you will learn:

- the goals/purpose of rhetorical analysis

- how to identify, understand, and gather information about a text,its speaker, its audience, and its situation

- the differences between explicit and implicit claims and arguments

In your next major essay, you will analyze an argument that is part of your chosen controversy’s discourse. Before guiding you through the steps of rhetorical analysis, we want to begin this chapter with a quick definition.

A rhetorical analysis is any effort to explain text-based persuasion with reference to audience and situation. You’ve already written one kind of rhetorical analysis. While mapping your controversy, you explained a series of arguments with reference to the audience (the stakeholders) and the situation (the stakeholders’ interests, the controversy’s history, the community’s values and beliefs). In this unit, you will write another kind of rhetorical analysis. Instead of focusing on a controversy, you’ll focus on one text—one article, one interview, one video or image. Instead of explaining how several viewpoints fit together in a conversation, you’ll explain how the reasons and the evidence fit together in a single argument. Instead of showing how the viewpoints move the controversy in one direction or another, you’ll show how the reasons and the evidence move the audience to believe one thing or another.

Writing a rhetorical analysis is beneficial to you in many ways. First, this kind of thinking will help you to look at sources and information in critical ways. Second, this kind of thinking will prepare you for writing a persuasive argument. Rhetorical analysis is strategic. It helps people understand the situation and the audience in order to be more persuasive. After mapping a controversy and analyzing an argument, you’ll be prepared to persuade an audience.

There’s another way to think about rhetorical analysis, something to keep in mind as you strategize. Rhetorical analysis is ethical. Rhetorical analysis can teach us to be more understanding of those with whom we disagree. And rhetorical analysis can teach us to be critical of those with whom we agree.

To analyze an argument that doesn’t persuade you, you must take the reasons seriously. And you must think carefully about why those reasons would move a group of reasonable people. So the first step in rhetorical analysis involves putting aside your own beliefs. Your question is not, “Do I find this argument convincing?” but instead, “Why would these people find this argument convincing?” Since your aim is to answer this second question, you cannot dismiss the audience or the argument as simply “wrong” or “wrong-headed.” Even though you may not agree, you do have to listen carefully, so that you can understand and then speak to different people with different perspectives. This consideration helps develop effective discourse that can solve complex problems.

If you’re analyzing an argument that persuades you, then you have already listened considerately. In this case, rhetorical analysis will help you to listen critically. Your question now becomes, “How does this argument persuade someone like me?” Once you see that your own beliefs are based on someone else’s persuasive efforts, you may feel a little less committed to that viewpoint. Just like people you disagree with, you base your beliefs on persuasive arguments. And just as the considerate person won’t go to war with someone they understand, the critical person won’t go to war over something they question. Being critical doesn’t mean you have to give up on your beliefs, nor does being considerate mean that you have to change your mind. You can remain committed while listening considerately and believing critically. This practice, too, is part of effective discourse that can solve problems.

The Basics of Rhetorical Analysis: Speaker, Audience, Situation, Text

Any sort of analysis requires that you take something apart. Analysis begins with disassembling and labeling. The next three chapters introduce you to techniques for doing that. In order to teach you how to disassemble an argument and label its parts, we will define the parts of an argument and we will tell you how to find those parts. The four major parts that you must identify and label in any rhetorical analysis are the speaker, the audience, the situation, and the text.

The Speaker

The speaker is the person, the organization, or the company trying to persuade. Sometimes it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly who the speaker is. Corporate advertisements, for instance, are often produced by marketing firms, even though they speak for the companies they represent. Is Nike or Wieden+Kennedy telling you to “Just do it”? It’s often easiest and best simply to assume that the speaker is the person or the group identified in the argument: Whoever is presented as the speaker is the speaker. In a Nike advertisement, therefore, the Nike corporation is the speaker. An introductory-level rhetorical analysis, such as the one you must write, can settle on the ostensible speaker (the person or organization who seems to be trying to persuade). But a more sophisticated rhetorical analysis might distinguish between the ostensible speaker, the real speaker, and the implied speaker. To return to our earlier example, the ostensible speaker in a Nike shoe commercial is Nike. The real speaker is the advertising firm (Wieden+Kennedy). The implied speaker is the star of the commercial, the athlete who runs up a flight of stairs and breathlessly declares, “Just do it!”

For the time being, we encourage you to focus on the ostensible speaker—the person or organization presented in the text as the persuader. Hereafter, we will simply use the term “speaker.” And we suggest that you divide your knowledge about this speaker into two categories: invented and situated. There is the information you learn about the speaker from the text itself. This is invented information because the speaker presents it in the body of their argument. Speakers use invented information to present themselves in the best possible light. For example, the speaker may reveal that they know a lot by citing expert sources; they may reveal that they are part of a community by referencing insider information; they may show that they care about certain things by saying, “Like you, I value education and family.” On the other hand, there is information that the audience is likely to know about the speaker before reading the argument. This is situated information because it is established before the speaker begins to persuade. You can find situated information about the speaker by looking for articles about the person’s or the organization’s reputation. Other arguments by this speaker can also teach you about this person’s or this organization’s reputation.

The Audience

The audience is who is listening to an argument. Audiences can be narrow and also infinitely vast depending on the text. For the purpose of rhetorical analysis in this course, we will think in terms of target audiences: who, specifically, the speaker intends to listen to their argument and who, specifically, the speaker intends to persuade.

In Chapter 1, when we were discussing stakeholders—their beliefs, values, and interests—we presented some basic terms that explain who an audience is and why they might care about an issue. These same terms can explain why people might find certain reasons persuasive. For instance, an audience that values the environment is more likely to be persuaded by an argument against hydrofracking that points to environmental damage. An audience interested in keeping health insurance costs low is likely to be interested in—that is, persuaded by—a plan that promises to reduce premiums. And an audience that believes violent crime is not associated with personal consumption of marijuana is more likely to accept the assertion that legalizing cannabis will not lead to a spike in crime.

Research, as we explain above, can teach you about the speaker; it can also teach you about the audience: their beliefs, values, and interests. Particularly, you can look at two types of sources: (1) direct feedback from the audience and (2) other arguments written to this audience. If members of the audience respond to an argument by saying, “yes, we agree,” then you can look at their reasons for agreeing. Imagine, for example, that a newspaper editorial tries to convince a group of Illinois residents that they should not vote for a candidate for the U.S. Senate because that candidate doesn’t live in Illinois. They try to convince their readers this candidate is a “carpetbagger”—someone who opportunistically moves to an area to win an election. Such an argument presumes that the audience values home-state residence. Imagine, also, that many voters write letters to the editor to say, “We don’t care about where they live. We only care that they represent our beliefs in the U.S. Senate.” The audience’s response indicates that, instead of valuing a candidate’s residency, they value the candidate’s positions. As a result, they are not persuaded. There is strategic value to understanding why this audience is not persuaded. The speaker could, for example, rework the argument to appeal to the audience’s values: “Since the candidate doesn’t live in Illinois, they won’t consistently understand what the community wants, and eventually, their positions will not reflect what is best for our state. Right now they may say things that we like, but later they will not.”

Another way to learn about an audience’s values, interests, and knowledge, is to look at other arguments published in the same venue. If you’re reading an article published in the Austin American-Statesman, you can assume that this newspaper’s audience shares its political bias. By reading editorials published in this newspaper, you can figure out whether the audience is liberal, conservative, or moderate. You can figure out what concerns these people. You can determine what they know (since they learn from the articles in the newspaper).

Brief Exercise: Find an article related to a controversy you’re interested in or refer to one offered by your instructor. Summarize the argument, and describe the audience by completing the following templates:

- This article assumes that the audience already believes ____. This is evident when the editors say, “_____.”

- This article assumes that the audience already values ____. This is evident when the editors mention ____.

- This article assumes that the audience shares an interest in ____. This is evident where the editors discuss ____.

When you complete these sentences, you will have a fair description of the intended audience for this argument—the people whom the speaker is trying to convince. But intended audiences often fail to match up with real audiences, the people who actually read an argument. You can learn about the intended audience by looking at the text itself. You can learn about the real audience by looking outside the text. We suggest two sources:

- The comments posted by actual readers. Online sources often include comments in the footer, below the article. Print sources often solicit responses that appear in other print formats. Letters to the editor, for example, are short pieces written by readers in response to specific articles.

- Other opinion articles on similar subjects found in the same venue.

Using the information you find in the readers’ comments answer these questions: What do you think a specific reader believes or values? What are his expressed interests? Based on your research into other articles, what do you think the typical reader of this magazine, newspaper, or website believes or values? What are they interested in? Finally, do the beliefs, values, and interests identified as belonging to this article’s intended audience match those of its real audience?

The Situation

An effective argument must speak to history and to exigency. These two factors constitute what we call the situation. For instance, if you want to build an argument against providing federal disaster relief to victims of tornadoes in the Midwest, you will have to consider the past efforts to provide federal disaster relief to hurricane victims on the East Coast and the Gulf Coast. Your audience will likely know this history, so they will expect you to discuss it: Why provide federal support for hurricane relief but not for tornado relief? Another component of history is the exigency, the immediate event or argument that has prompted someone to speak or write. It may be a recent event (a tornado that destroyed a town in Oklahoma). It may be a recent argument (a governor’s public demand that the president declare this town a federal disaster area). That exigency might combine with history. People’s experience of a recent tornado might combine with their knowledge of past tornadoes and their memory of federal money previously spent rebuilding in tornado-prone areas. This combination of recent events and past experience might prompt the community to debate federal disaster relief for the area. The history and the exigency, like the audience and the speaker, can be researched.

The Text

So far, we have used the term “text” to reference the thing you will analyze and we have mostly referred to written texts like articles and blogs. “Text,” however, can refer to any object that makes an argument or sends a message, word-based or otherwise. Rhetorical analysis applies to anything intended to persuade: a printed editorial, a graphic image, a company logo, a video commercial, a movie, an item of clothing, an art installation, a protest sign. The first question to ask when analyzing any text is: Does the speaker make this argument implicitly or explicitly? We introduced the terms “implicit” and “explicit” in Chapter 2, but here’s a quick refresher. An explicit claim is stated openly. The speaker tells you to believe, feel, or do something. An implicit claim is suggested. The speaker tells you many things, and you arrive at the conclusion that the speaker wants you to accept. Many texts hold both explicit and implicit claims. A Facebook ad, for example, that says “Life is better with a Yeti” is explicitly arguing that Yeti tumblers improve quality of life. The ad, however, is implying a number of arguments. One of these arguments is that, because they are reusabe, Yeti tumblers support sustainable, eco-conscious lifestyles that are better for life on this planet. The ad is also implicitly arguing that, because of these qualities, they are worth spending $35.

This distinction between “implicit” and “explicit” points to the first key rhetorical element in any text: the claim. The claim is the principal idea that the audience should accept after encountering an argument. Claims come in many shapes and sizes. We suggest you think of claims in three ways. Some claims encourage the audience to believe. Some claims ask the audience to feel. And some claims petition the audience to act. When you are analyzing an implicit claim, you must state it in your own words since the speaker does not state it directly. You can use the following templates to guide you:

- The argument tells the audience to believe that ____.

- The argument encourages the audience to feel ____.

- The argument enjoins the audience to do ____. If you are analyzing an explicit argument, the claim will be stated somewhere in the text. You can simply quote it. Here are a few rules of thumb that will help you to separate implicit from explicit claims:

- Arguments made in political and legal forums (opinion pages in the newspaper, congressional hearings, TV talk shows, courtrooms, corporate boardroom meetings) tend to be explicit. Arguments made in forums that aim to inform or entertain (documentary films, TV advertisements, movies, images, popular songs) tend to be implicit.

- Arguments that call for action tend to be explicit.

- Arguments that encourage feeling tend to be implicit.

- Arguments made to audiences who are inclined to agree with the speaker tend to be explicit.

- Arguments made to audiences who are inclined to disagree with the speaker tend to be implicit.

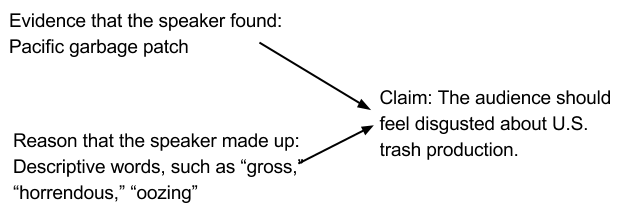

Everything in the text apart from the claim either supports or undermines the claim. The speaker wants to move the audience to believe, feel, or do something. So they give reasons to support the claim. As you will learn in the next chapter, anything can be a reason. In a speech, a calm tone of voice can ask you to trust the speaker, and this trust can lead you to believe what the speaker says. In a movie, the music can make you tense, so you become more susceptible to being frightened. Reasons, as we’ll explain in Chapter 5, are things that the speaker makes up. Evidence, on the other hand, is the stuff the speaker finds. If a speaker wants to make you feel disgusted by the amount of trash that U.S. residents produce, They might, for example, show you the Pacific garbage patch. They didn’t make up the garbage patch. They found it. They might use especially moving language to describe the garbage patch: “gross,” “horrendous,” “oozing.” This language is a reason, one they create or makes up, to further the claim: You should feel disgusted about how much trash U.S. residents produce.

As shown above, the reason and the evidence work together to convince the audience that they should feel a certain way. In the next two chapters, we will talk in much greater detail about reasons and evidence. For now, as you initially consider the text you want to analyze, we encourage you to separate the claim from the rest of the material in the argument. If you can, try to classify anything that’s not a claim as a “reason” or as “evidence.”

Chapter Assignment: Identifying Parts of an Argument

Below, we offer a table that categorizes the kinds of evidence (both textual and contextual) that you can find to inform your analysis of the speaker, the audience, and the situation. We also offer suggestions for where to look to find such evidence in this table:

| Rhetorical Situation | Textual Evidence | Contextual Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Speaker | Invented information about the speaker: moments in the text when the speaker identifies their qualities, interests, or knowlege; aspects of the text like writing style or citations that tell you about the speaker’s experiences or interests | Situated information about the speaker: biographical information that the audience is likely to know or can find out. This info can be found by looking at other texts the speaker has composed or texts composed about them |

| Audience | Information about the intended audience: The values, interests, and beliefs that the argument appeals to all belong to the intended audience | Information about the real audience: The values, interests, and beliefs that belong to real people who encounter this argument. Gather this information by looking at readers’ responses to the argument and by looking at other arguments that the real audience finds persuasive |

| Situation | Information about the situation that is mentioned in the argument itself | Information about the situation that can be learned by finding other sources |

Once you’ve selected the text you want to analyze, try to find one bit of textual evidence to fit in each of the boxes in the “Textual Evidence” column. Try to find a quote, paragraph, or phrase that demonstrates invented information about the speaker, a description of the intended audience, or a description of the situation. Then try to find secondary texts with information to fill in the boxes in the “Contextual Evidence” column, such as an article, encyclopedia entry, or web page that demonstrates situated information about the speaker, information about the real audience, or information about the situation that is not mentioned directly in the text.