Chapter 5: Analyzing Reasons

In this chapter, you will learn:

- how to distinguish between claims, reasons and evidence in an argument.

- how to distinguish between three kinds of reasons (to trust, feel, and believe).

- how to connect reasons given in an argument to the claim(s) and evidence in an argument.

Arguments happen in places—at parties, in magazines, on websites. And the place matters a lot. One argument will be very well received in one place but not in another. Your friends will likely agree when you say that a professor should move an exam date so that you can go home early for spring break. On the other hand, saying the same thing to the professor would not persuade. In the previous chapter, we offered tools for analyzing situation and context, the places where arguments happen. Context is the most important rhetorical element because the best argument in the worst place or at the wrong time will fail miserably.

The next two chapters offer tools for analyzing the text—the parts of an argument and their relation to one another. This chapter will focus on reasons, and the next chapter will discuss evidence. Both reasons and evidence encourage an audience to believe a claim. Speakers invent or make up reasons. Speakers find or research evidence. When we say that reasons are invented, we don’t mean that they are fictitious or false. We mean that reasons come from creativity. Evidence comes from research. Speakers generally find their reasons first. When trying to think of ways to appeal to an audience, ask yourself, “How can I get these people to trust me? To feel a certain way? To do something?” The answers to these questions lead you to possible reasons. If the reasons by themselves are not convincing, then you may need to find evidence that will further support your reasons.

To illustrate, let’s go back to our earlier example: trying to convince a professor to delay the mid-term exam so you can go home early for spring break. For this audience (the professor) in this situation (the classroom), your argument is not convincing. So you need to think of some good reasons. You brainstorm for a little while. Here’s what you invent:

- Delaying the exam will let you (the professor) go home early too.

- Delaying the exam will let us (the students) study over spring break, so we (students) will be better prepared for the final.

- Delaying the exam will let us (the students) spend valuable time with our families.

You decide that the third reason is most likely to convince your professor because you’ve heard them explain that they care about student performance.

So you go to class, and you state your claim followed by your reason. When they hear your argument, your professor chuckles a bit and responds, “You won’t study over spring break; you’ll forget a lot of what you’ve learned; and you’ll do even worse on the mid-term.” Undaunted, you decide that you will find some evidence to support your reason. How about a survey? You ask all the students in the class if they studied over Thanksgiving break. Seventy-two percent (72%) report that they did. Or maybe you find some examples from previous classes. Last fall, three biology seminars had tests right before Thanksgiving break, and two had tests right after. You learn that students in the seminars with exams after Thanksgiving break earned much higher grades than students with exams before Thanksgiving break. Of course, we’re just making up this evidence as an example. It may be entirely false, and false evidence will make an argument embarrassingly unconvincing. Liars invent evidence. Convincing speakers invent reasons; then they find evidence.

Sometimes, reasons do not require evidence. You don’t need to prove to your professor that letting students take the exam after spring break will allow them to leave town a day early too. We will discuss the relationship between reasons and evidence more fully in the next chapter. For now, we encourage you to make this distinction: Speakers invent reasons, but they find evidence. And we encourage you to notice that evidence is typically—but not always—introduced to support reasons.

Like many guides to rhetoric and argumentation—some over 2,000 years old—we divide reasons into three categories: reasons to trust the speaker; reasons to feel a certain way; reasons to believe a certain thing. An effective argument will offer some combination of all three. Next, we define each type of reason, and we explain how it contributes to an argument’s efficacy.

Reasons to Trust

The first thing that a speaker must do is to win the audience’s trust. If you don’t trust someone, you won’t believe what he says, no matter how well researched, persuasive, or moving the message might be. In fact, a persuasive argument coming from someone you don’t trust is likely to be doubly rejected. You might think that such an untrustworthy person has persuaded you by lying and manipulating your emotions. If you do trust someone, on the other hand, then you will be more likely to feel what they ask you to feel and to believe what they ask you to believe.

In the previous chapter, we discussed two types of information that you can learn about the speaker: invented information and situated information. The situated information is the evidence—the information that the audience already knows about the speaker. Knowing that someone is a research scientist, a university professor, an award-winning journalist, or a famous inventor will make an audience more inclined to trust what they say. But there are other invented reasons to trust a speaker. Even if we don’t know a person’s expertise beforehand, we can pay close attention to the information that he presents. If he offers plenty of factual information, cites authorities, and seems to know the subject, then we have good reason to trust him just as we would an expert authority. A speaker who has both the situated and the invented expertise—a renowned research scientist who speaks authoritatively—will surely gain the audience’s trust.

When you are looking for the textual elements that earn an audience’s trust, we encourage you to find the situated information about the speaker, but we also encourage you to look for the invented reasons. Within the text, a speaker can show that they are smart and well informed by demonstrating several things:

1. Knowledge of the subject: Someone who shows you that they’ve learned a lot of information about a subject is someone you will likely trust as an authority even if they don’t have the credentials.

2. An ability to respond appropriately to the situation: An effective communicator knows when to speak and in what manner. We make decisions like this constantly in our daily lives: when we compose emails to our bosses and begin with “Dear Mr. Caulfield,” call our grandmothers and avoid cursing and expletives, and talk to toddlers about babas and milkie and Elmo. In this textbook, we the writers have made conscious decisions about our style to show that we understand the classroom situation. Since we’re writing to students, we have chosen to write in a somewhat informal style. We use first- and second-person pronouns (we, you); we use contractions (don’t, isn’t); we throw in the occasional sentence fragment (“How about a survey?”).

3. Membership in a community: We tend to trust people who belong to our community because they share our interests, our values, and our concerns. The speaker might show the audience that she belongs to their community by referencing common knowledge. By mentioning information about themselves or their past. By confessing interests and values that the community will recognize.

4. Demonstration of goodwill: We trust people who show us that they have our best interests at heart. The speaker might directly say that they want to help the audience. Or they might show, through some other gesture, that they want the audience to prosper. In this textbook, we try to demonstrate goodwill by writing in a friendly manner. A clear and somewhat informal writing style shows that we care about your education. We don’t want to flaunt our erudition with abstruse verbiage. (If we did, we’d use more words like “flaunt,” “erudition,” and “abstruse.”) We want to teach so that you can learn.

These attributes make a speaker seem credible and trustworthy. Keep in mind that different audiences will value different attributes. Some audiences will value a speaker they recognize as part of their community more than a speaker who demonstrates knowledge of a subject.

In our discussion, we have focused on elements of writing that can deliver these reasons, but we want to emphasize that other elements in an argument can give the audience a reason to trust the speaker. Music in the background of a car commercial can show the audience that the company knows their taste and belongs to their community—country and western for a commercial that airs in rural Texas, hip-hop for one that plays in Houston. A U.S. flag pin on a senator’s lapel shows that they belong to the national community. Wearing a fleece pullover or a casual shirt (instead of a suit) while touring a disaster site shows that a U.S. president can dress appropriately to the situation. We trust them because they are ready to roll up their sleeves and fix this mess. A reason to trust can be any element that encourages the audience to imagine the speaker as an authority, as a member of the community, as someone who understands the situation, or as someone who cares about the audience.

Further Discussion: Do a quick Google Search to find an viewpoint article related to your controversy. Is the author’s writing style appropriate to their subject? Do they write about a serious matter in a joking way? Do they show you that they belongs to your community or to the audience’s community? Does they seem informed about his subject? How do they show you that they’ve thoroughly researched this topic? Notice also that many opinion articles published in newspapers include a brief biography of the author. Does the biography (a bit of situated evidence about the speaker) give you additional reason to trust the author?

Reasons to Feel

While reasons to trust focus on the speaker, reasons to feel focus on the subject. Effective communicators appeal to their audience’s emotions: fear, anger, sadness, passion, pride, love, insecurity, honor, belonging, confidence, isolation, empathy. In verbal media like books, articles, and speeches, the speaker uses words, phrases, diction, syntax, voice, and rhythm to create emotions that can persuade. In graphic media like photographs, artists use color, lines, framing, angle, and more to create emotions that can persuade. In multimedia texts like movies and ads, directors and editors use color, light, dialogue, voiceover, music, timing, and more to generate feelings.

Further Discussion: Commercials for products work because they create insecurity and/or desire, and then they present their product as the “cure” for both emotions. With GIFs like the one below, audiences acknowledge that they know they have been manipulated by a product, but they don’t care. They want it anyway. Think of a time you knew you were being persuaded to buy something and bought the thing anyway. What about the product or the advertisement or presentation of the product made you want it anyway? What did the marketers do so right? What emotions other than insecurity and desire do you think marketers harness and create?

Imagery and Description

Images are a powerful strategy for creating emotions. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech is an example of how words can create images in our heads that persuade us. Through his language and voice, King paints a picture of a world better than the one we live in and uses it to argue for steps that must be taken to create that world. Vivid descriptions can be lengthy like King’s or held in a few words: Example: “Sneak home and pray you never know the hell where youth and laughter go” written by Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967), “Suicide in the Trenches.” Sassoon was a decorated WWI soldier who returned home to write nightmare descriptions of soldiers’ experiences to argue against governments invested in the profitable “glory” of war. Imagery can also, of course, be literal images used by a communicator: photographs, film, art, illustrations, etc. Images from September 11, for example, persuaded most Americans of the need for war. Sometimes, image-based symbols and references are enough to generate feelings; consider, for example the power of the “Like” thumb on Facebook (and other emojis) to convey and cause an emotional. Word-based and picture-based imagery often work differently. With words, a speaker can direct an audience how to feel about a thing by focusing their attention and characterizing their description with super specific language (“Sneak,” “pray,” and “hell” are very specific words that reference very specific images and conjure very specific emotions). Picture-based imagery, meanwhile, often implies emotion rather than directly stating it; there is more room for interpretation and more room for the audience’s memory of their own experiences to bubble in and produce an affect.

Further Discussion: Often, vivid description of a real example works two ways. The example is evidence that convinces the audience to believe. The vivid description of the example is a reason to feel. Take the following scenario, and discuss it with your classmates: Imagine you’re writing an article that promotes government-subsidized preschool for needy families. You want to show that pre-school deserves to be supported by taxpayer money because it helps kids do well in their first years of school. You could give a statistic: “Studies show that kids who have one year of preschool get on average 65% higher marks on their first- and second-grade benchmark tests for reading and math.” That statistic is convincing evidence in support of a reason to believe, but it’s not very moving. Think of or find an example that you can vividly describe to move your audience. Try to get your audience to feel happy for one plucky kid who got a leg up. How would you vividly describe that kid’s story?

Values

Images are based on tangible, physical things an audience can see or has seen. Values are different in that they are ideas that are important to us. A value is not tangible. You can’t pick it up, look at it, or even touch it. But you care about it nonetheless. Injustice makes you angry. Liberty makes you proud. Ingratitude makes you resentful. None of these things can be touched or photographed. But a speaker can use values to give the audience a reason to feel that a person, event, or proposition is right or wrong—is in accordance with a particular value or against it.

Speakers often use values to motivate reaction and action. For example, for Americans, freedom of speech is a core value, crucially tied to their sense of identity. The idea of freedom of speech creates many emotions: pride, hope, love, exceptionalism, dedication. For others, it might create a sense of trepidation, skepticism, or even derision. Speakers across the political spectrum have leveraged these emotions to their ends in public debates to convince an audience whose “side” they should be on. In the last few years, we have seen freedom of speech come up as a value under threat in multiple debates: prayer in public schools; the regulation of content by media platforms like YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and TikTok; an athlete’s right to take a knee during the national anthem; and the right for protestors to assemble peaceably.

Honorific and Pejorative Language

Speakers use honorific and pejorative language to enhance the emotional impact of an image or a value. Honorific language praises something that people already care about (or that they should care about). “Liberty,” described honorifically, becomes “our cherished liberty.” The Texas Capitol becomes a “magisterial statehouse.” Pejorative language denounces something that people should already despise. Described pejoratively, protestors become “thugs,” immigrants and refugees become “illegal aliens,” state representatives become “bitches” or “Nazis.” So far, we have focused on language, but we should emphasize that “honorific” and “pejorative” can apply to many efforts at enhancing the emotions that people already feel. A photographer who wants to honorifically present a public figure will capture them in the best light. A photographer who wants to pejoratively depict the same public figure will zoom in to capture all their wrinkles or in the middle of making a weird face.

Reasons to Believe

Like reasons to feel, reasons to believe focus on the subject. Rather than asking the audience to experience an emotion, however, reasons to believe ask the audience to arrive at a conclusion. Many theorists of rhetoric will say that a reason to feel is an “emotional appeal,” and a reason to believe is a “logical appeal.” We don’t say “emotion” or “logic” because such terms imply that reasons to feel should be less persuasive than reasons to believe. Calling them “emotional” and “logical” suggests that one type of appeal manipulates the audience. Nothing could be further from the truth. Images and values can both be reasonable, if they deserve to be mentioned and if they apply to the situation. Similarly, a causal or a definitional argument (both appeals to reason) can be foolish. I can say that you should oppose gay marriage because, when we allow homosexuals to legally wed, we open the door to laws that allow people to marry barnyard animals. This, believe it or not, is a “logical” appeal. It asks us to believe that gay marriage will cause humans to marry cows. I can similarly say that you should not feel so attached to traditional marriage because it is a recent invention designed to support the whole wedding-planning industry. Marriage is a scam to sell overpriced diamonds, bad cake, and white dresses. This is a definitional argument, asking you to put traditional marriage in the same category as other tawdry money-making efforts. We suggest that both of these arguments—the causal and the definitional—are unconvincing even though they’re reasons to believe. Our point is simple: Reasons to believe can be just as good and just as bad (just as reasonable and just as unreasonable) as reasons to feel.

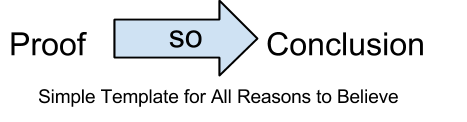

Reasons to believe can be broken up into different types. In Chapter 8, we explore a few such types of reasons to believe. In this chapter, to help you analyze reasons to believe, we will emphasize the basic form that they all share. Every reason to believe asks the audience to conclude something based on something else. A speaker asks the audience to conclude that another full-blown U.S. war in the Middle East would be an unwinnable mess. They supports this argument by comparing a war in the Middle East to the Vietnam War or to the more recent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. A speaker asks the audience to conclude that the president of a company should be blamed for its corruption based on the common knowledge that a fish rots from the head down. A speaker asks the audience to conclude that people over the age of 18 should be allowed to drink alcohol because these same people can vote in elections and serve in the military. In each of these cases, you have two elements: a conclusion and a proof. The proof leads to the conclusion. You can paraphrase each reason to believe using a simple template:

Here’s how the above reasons to believe translate into the simple template:

- A war in the Middle East would be just like the Vietnam War (or the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq), SO a war in the Middle East would be an unwinnable mess.

- A fish rots from the head down, SO Kenneth Lay was responsible for all the corruption at Enron.

- We let people over the age of 18 vote and serve in the military, SO we should also let them drink alcohol.

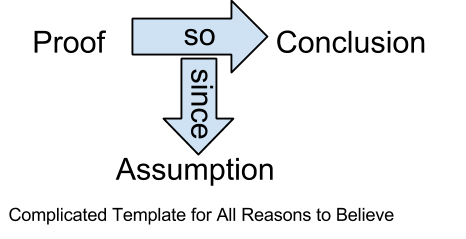

While the proof and the conclusion are generally easy to locate, there is often a third hidden element, the assumption. This third element is much more difficult to identify because it often remains unstated. Most reasons to believe assume that the audience already believes something else. Based on this assumed belief combined with the proof, the speaker asks the audience to accept the conclusion. Our simple formula, therefore, becomes a bit more complicated:

Here’s how our reasons translate into this complicated template:

- A war in the Middle East would be just like the Vietnam War in so many ways, SO a war in the Middle East would be an unwinnable mess SINCE all wars that share these qualities must be messy and unwinnable.

- A fish rots from the head down, SO Kenneth Lay was responsible for all the corruption at Enron SINCE as CEO, Lay knew about and directed all of the company’s activities.

- We let people over the age of 18 vote and serve in the military SO we should also let them drink alcohol SINCE the privilege to drink alcohol should be given when we confer upon citizens their right to vote and their duty to military service.

Reasons to believe can be the hardest to analyze for two reasons. First, they have the most moving parts. Reasons to trust include efforts to convince the audience that the speaker belongs to a community, is knowledgeable, smart, and good-willed. Reasons to feel include the presentation of images and values (often in pejorative or honorific language). Reasons to believe include three interconnected parts: the proof, the conclusion, and the assumption.

Second, one part of a reason to believe (the assumption) is often not stated, even though it is integral. If the audience does not accept any of the above assumptions, then they will not draw the conclusions based on the proofs. Someone who doesn’t believe that all wars sharing certain qualities are just like Vietnam will retort: “Vietnam was a messy war to maintain a puppet government in Southeast Asia; Afghanistan was a difficult effort to establish a new democracy on the Afghan people’s terms; and putting troops on the ground in Syria would offer support to people who are fighting against a cruel dictator on the one hand and a violent theocracy on the other. So these are completely different scenarios.” Someone who doesn’t think that Kenneth Lay knew about Enron’s accounting gimmicks will say: “You can’t blame Lay for accountants secretly cooking the books. CEOs are figureheads of corporations; they don’t really know or direct everything that happens in the organization.” And someone who does not think the right to drink should be given along with the right to vote and the duty to serve will say: “Voting and military service are rights and duties of citizenship. They belong together. But drinking is a privilege, like driving a car, and it should not be given to people who won’t exercise the privilege responsibly.”

Though the assumption may be difficult to locate, it is a very important—maybe the most important—part of any reason to believe. The assumption connects the audience to the argument. If an audience rejects the assumption, then they will reject the conclusion.

Analyzing Reasons

Since the parts of an argument do not announce themselves as reasons, your job is to identify the persuasive elements in a text. We suggest identifying these elements first. Don’t worry about labeling them “reasons to trust” or “reasons to feel.” Just circle, underline, or describe the parts that you think the audience will notice. Then ask yourself, “Does this paragraph, this image, this sentence, or this video segment try to earn the audience’s trust, move their feelings, or guide their beliefs?” Once you’ve labeled each element a reason to trust, a reason to feel, or a reason to believe, you can explain how one reason relates to the other reasons and to the argument as a whole.

To help you further in your efforts at analyzing reasons, below we offer some general advice and pointers.

- Anything can be a reason. In the first part of this chapter, we tend to focus on bits of printed text, but we also want to note that any persuasive element can be analyzed as a reason to trust, to feel, or to believe: images, music, video clips, color schemes, design templates, and dress styles, and the like.

- Reasons often work together. As a rhetorical analyst, you must separate the reasons. But you must also show how the reasons work together. For instance, you might explain how the reasons to trust support the reasons to believe. Or how the reasons to feel support the reasons to believe. Or how the reasons to believe support the reasons to trust.

- One element in an argument can serve as multiple reasons. Several well-researched proofs can lead to one conclusion, thus forming a reason to believe. But these same proofs show the audience that the speaker is knowledgeable, thus forming a reason to trust. An image can move the audience to feel something. But that same image can serve as proof (an example) to support a general conclusion. Thus, one image can simultaneously be a reason to feel and a reason to believe.

Last, we want to explicitly mention the tasks that any rhetorical analyst must do in order to analyze a reason. First, you must locate the persuasive elements in a text. Then, you must identify each element as a kind of reason. Next, you must explain the intended effect on the audience. Finally, you must explain how this reason relates to the others in the argument.

Chapter Assignment

The following table breaks down the tasks you should complete whenever you analyze reasons in an argument:

| 1. Find the persuasive element | 2. Identify this element as a kind of reason | 3. Explainthe effect that this reason should have on the audience | 4. Explain how this reason relates to other reasons or to the principal claim |

| Johnson describes recent terrorist activities | Reason to feel | It convinces the audience to feel fear | The fear that the audience feels anout terrorism leads them to feel fearful about potential terrorists buying guns |

| Johnson explains that people who are currently under suspicion for terrorist-related activities can still purchase firearms without restriction | Reason to believe | It convinces the audience to believe that potential terrorists have access to powerful weapons | The belief that terrorists can buy weapons without restriction and the fear of terrorism both combine to support Johnson’s argument that people on the government’s “no-fly” list for terrorist suspects should also be restricted from purchasing firearms. |

Make a similar table about the text you’ve decided to analyze. You will probably find more reasons than you could possibly analyze in a 4–5 page paper. So think about which reasons are most important or most interesting, and focus on those in your analysis.