Chapter 6: Analyzing Evidence

In this chapter, you will learn:

- How evidence is used in arguments (to support reasons and/or claims)

- The most frequently encountered types of evidence, and their rhetorical functions

- How to identify and analyze rhetorical uses of evidence in arguments

In the last chapter, we discussed the reasons that a speaker can invent to support a claim. In this chapter, we will discuss how evidence is used to support reasons. For example, if you are trying to persuade your friend to prepare for an exam by studying a little bit every night rather than cramming, you might invent a few reasons:

- “Studying for exams a little bit at a time results in better grades, so you should study for thirty minutes every night this week.”

- “I’m a good student. You should trust my advice.”

- “You’ll enjoy your half-hour study sessions. They’re relaxed. Nothing is more pleasant than reading over your notes and practicing a few calculus problems while enjoying a chai latte at the coffee shop down the road. You could do that every morning!” In our imagined example, there is a reason to believe that certain study habits result in good grades, a reason to trust the speaker, and a reason to feel good about studying every day. The reason to believe seems a bit weak, however. Your friend may wonder, “How do you know that studying every day will lead to better grades? Do you know Eddie? That guy crams for every exam. And he’s a straight-A student!” Your friend has offered evidence—an example—to support their argument. As a result, they favor cramming. You can counter with evidence of your own: examples of people who study every day and proof that Eddie studies every day, despite what he says. All of your additional evidence supports that first reason to believe: Studying for exams a little bit at a time results in better grades, so you should study for thirty minutes every night this week

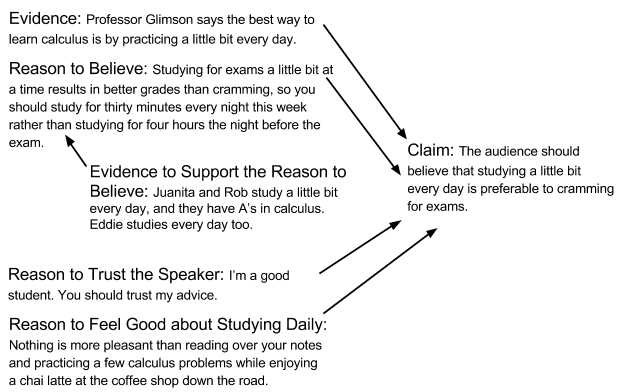

Often, evidence supports reasons, which themselves support a claim. Evidence, however, may also directly support a claim. Returning to our example, imagine that you add to your argument the following evidence: Your professor says the best way to learn calculus is by practicing a little bit every day. This evidence directly supports your claim that daily study is preferable to cramming. The diagram below illustrates how some of your evidence supports a reason and some of your evidence supports the claim.

We open with this example to explain the difference between reasons and evidence and to show you the basic steps that you should follow when analyzing evidence.

- First, separate the reasons from the evidence. The descriptions of reasons and evidence in this chapter and in the last chapter will help you to separate one from the other.

- Second, explain what the evidence is doing. Is it there to make a reason more convincing, or is it there to directly support the argument? Keep in mind that one piece of evidence can accomplish many things. The example of someone studying every day supports the reason to believe that daily study is effective. But that example also vividly describes an image of a person at Prufrock’s coffee shop smiling as they leisurely sip on a macchiato and finish last night’s calculus homework. Juanita’s image supports the reason to feel good about studying daily. The example accomplishes two rhetorical purposes, making the audience believe and encouraging the audience to feel.

- Third, explain why the evidence is needed. If an audience already accepts something as true, then further evidence isn’t needed to convince them. If an audience doubts that something is true, then evidence is necessary. But evidence doesn’t strictly address a dubious audience. It may help the audience to imagine something they cannot yet conceptualize. It may help them feel something more strongly. For instance, an audience may already dislike gun-related violence. But in order to gain their support for an assault-weapons ban, the speaker needs to make the audience feel horrified, so the speaker offers statistics about the number of people killed with automatic or semi-automatic rifles in the last three years. The argument doesn’t need to convince a doubtful audience. They already agree that many people die in gun-related violence, and they agree that it’s a problem. But they don’t feel strongly enough about these particular weapons. So the argument includes statistical evidence to incite the audience’s outrage.

While exploring these basic steps, this introductory gambit also demonstrates why the speaker’s knowledge is so important. Effective communicators do their research: Broad knowledge helps speakers connect with their audience; specific information helps speakers prove their reasons, claims, and overall argument with evidence. We do caution, however, against believing that, once a speaker knows the kinds of evidence, they can be persuasive. To be persuasive, a speaker needs to know the evidence itself. They must also know how to present the evidence in a convincing argument. Some speakers are extremely effective without offering a shred of researched evidence. This efficacy depends on the audience and what kind of evidence an audience recognizes as “true.”

Below, we offer categories that identify certain kinds of evidence.

Types of Evidence

Like reasons, evidence comes in all shapes and sizes. To make things even more complicated, we keep inventing new kinds of evidence. When you choose a major, you decide to study the ways of collecting evidence in biology, chemistry, history, or psychology. Since we cannot cover all or even most of the kinds of evidence, we will instead focus on a few of the more common types of evidence that you are likely to find in public arguments. These categories will help you to analyze the texts you’ve selected for your second major assignment.

Authority Figures

In Chapter 2, we briefly discuss authority. Authorities are the experts whom you can cite when you lack expertise. Let’s imagine you’re not a family psychologist, but you want to prove that adoption laws should favor traditionally married couples because they tend to raise well-adjusted children. You can quote a respected family psychologist.

Authorities are very useful, especially if the audience recognizes and trusts the expertise of the authorities. But if the audience doesn’t know about such things, then the authorities must be introduced to show why they deserve the audience’s trust. A speaker may introduce an authority by saying, for instance, “According to respected family psychologist Pilar Hernandez, traditionally married couples who adopt are more likely to raise emotionally adjusted children.” If the audience still won’t trust Hernandez’s authority, then additional introductory information may be needed: “According to Pilar Hernandez, a respected family psychologist who has written several books on the subject of children’s emotional development in adoptive families, couples in a traditional marriage are more likely to raise well-adjusted children.” To counter such an argument, you should find authorities who say the opposite: psychiatrists who find that an adopted child’s emotional development has no connection to the parents’ gender or sexuality.

An authority can speak outside of his expertise and still be trusted. U.S. presidents and governors often stand as authorities on morality, even though they are experts on government. Religious leaders stand as authorities on politics, even though they are experts on theology. And athletes stand as authorities on everything from parenting to world affairs, even though they are experts on professional sports. Not long ago, a former vice president with training as a lawyer gave world-renowned lectures on global climate change. And a real-estate magnate became a major contender for national political office. Al Gore was no expert on the subject of climatology, but people trusted what he had to say. Donald Trump is no authority on international affairs, yet people have supported his campaign for the U.S. presidency.

Of course, an audience should trust an authority based on their expertise, but this doesn’t mean that people trust an authority only in the area of their expertise. People often conclude that a person’s excellence in one aspect of life will translate elsewhere. It is for this reason that we often elect military and civic leaders to political office. And we ask religious leaders for advice about raising a family. When rhetorically analyzing a speaker’s use of authority as evidence, you should worry less about whether the authority is really an expert on a given subject and instead focus on whether and why an audience would trust this authority. If the audience will not initially trust this person, then what can the speaker say to show that the authority deserves the audience’s trust?

Testimony

Testimony and authority are similar. Both rely on something someone else said. The following two examples capture the difference between authority and testimony:

- A medical doctor who works in a drug-treatment facility says that abusing prescription medication often leads to the abuse of illegal narcotics. They are an authority, someone who has expert knowledge.

- An addict says that they started using OxyContin to treat a neck injury, but they graduated to heroin when they discovered that it satisfied their craving more effectively and more cheaply. The addict is no expert. They haven’t studied narcotics, nor have they worked for years treating addicts. But they have personal experience. The addict offers testimony, a personal account of something they lived or witnessed firsthand.

Testimony can be more convincing than authority. Experts can sound detached. They have a lot of information, but they may not have experienced anything directly, so their knowledge can seem sterile. We trust people who have seen and survived. When you want advice about how to get over a break-up, you’ll ask your older sister before you ask a trained psychologist. Your sister, as you know, has experienced heartache. The psychologist read a textbook about emotional distress due to infidelity. When you want advice about how to write a poem, you will ask a poet, not a literary critic. The poet has wrestled with words. They know firsthand what it’s like to struggle with a line or a stanza. The literary critic knows about some poets who struggled with lines or stanzas.

Both testimony and authority can support reasons to believe. These two forms of evidence can also offer reasons to trust a speaker. Audiences trust authorities because of their expertise. A speaker who can cite such an authority borrows the authority’s expertise and earns the audience’s trust. Audiences trust testimony because it comes from people with firsthand experience. By citing the person who saw things firsthand, a speaker can borrow that experience and earn the audience’s trust. Even if you don’t know or haven’t seen, the audience can trust you because you’ve at least spoken to people who know and have seen.

Testimony is particularly well suited to move the audience’s emotions. We will not be moved to tears of joy when a psychologist tells us that wedding ceremonies elicit gleeful sentiment in 98% of the parents who attend. But we may choke up as we listen to the father of the groom describe what he felt while watching his child say their marriage vows. Because testimony has such emotional impact, many newspaper stories open with something journalists call a “human interest lead” before offering statistical information. A journalist may write a paragraph or two describing and quoting a disaster victim or homeless person. Then, they might present statistics about the number of people who lost their homes to a tornado or the number of people sleeping on the streets tonight.

Examples

Examples are particular people, things, moments, or places that the speaker brings forward. Examples can serve many rhetorical purposes. An image of a few starving children in a faraway country can move the audience to feel pity. A description of a man’s journey across the Pacific Ocean on a raft can move the audience to believe that ancient peoples could have migrated by sea from the Pacific islands to California. A summary of a book that someone has written can earn the audience’s trust that the speaker is an authority. Each of the previous sentences offers a hypothetical example—something specific that didn’t actually exist—and each of these hypothetical examples aims to convince you to believe the broader claim at the beginning of this paragraph: “Examples serve many purposes.” Our point is that examples don’t have to be vivid. They don’t have to be typical. And they don’t have to be real. An example only has to be specific: one person, one event, one place, one thing.

Different kinds of examples typically serve different rhetorical purposes. Here are some of the more common rhetorical uses of examples:

- Vivid examples typically aim to move the audience’s emotions by offering an image.

- Hypothetical (not real) examples typically aim to show the audience something that they have not yet imagined.

- Real examples, especially when offered in abundance, typically aim to convince the audience to believe that something is possible or even typical. Because it is so versatile, the example is one of the most common forms of evidence. Even statistical data are an elaborate collection of examples to prove that a trend exists. How do you know that women favor one political candidate over another? The statistician offers a survey—examples of 1,000 women, randomly surveyed: 57.2% (572 specific women) saying they would vote for Emily Chao.

Since examples are so common and so versatile, it is important not only to identify an example but also to explain its rhetorical purpose. Does the example support the principal claim or one of the reasons? And how does the example offer that support?

Sign

A sign is an indication that something may exist or be true. Clouds in the sky are signs that it will rain. Wet pavement is a sign that rain has recently fallen. Neither clouds nor the wet street is an example of rain. But they can indicate rain. Sometimes signs are quite trustworthy. Sometimes not. A sign of pregnancy is weight gain. But it’s not a very trustworthy sign, since people’s bodies change for all sorts of reasons. A better sign of pregnancy is lactation. But that’s not foolproof either. To determine whether a sign will be persuasive, you should think about the audience. Will they accept something as a reliable indication of something else? A scientist must wonder whether the indication is reliable. A speaker—and a rhetorical analyst—must wonder whether the audience will believe that it’s reliable.

Signs, like examples, can serve many rhetorical purposes. Here are two of the more common rhetorical uses of signs:

- Indications of fact: Signs often encourage the audience to believe that certain things exist or have existed. How do we know the economy is doing better? Look at the stock market’s recent performance. How do we know the economy is not improving for most people? Look at the levels of unemployment. How do we know the economy has not done well for the last few years? Look at the slow growth in gross domestic product.

- Harbingers of the future: Signs often ask the audience to feel something—often hope or fear. Omens, for example, are bad signs. Many believe that a dip in the consumer confidence index is an omen of another economic downturn. Others believe that a high trade deficit is an omen of a country’s impending economic decline. As the above examples illustrate, signs are far from certain. But their uncertainty should not lead us or anyone else to doubt them altogether. Much contemporary science relies on signs. The chief evidence for the existence of other planets is the example of our own solar system (which must be typical) and two signs: a visible wobble and an occasional shadow that we can detect when observing distant stars. The chief evidence for global climate change is a range of signs: increased rainfall in some regions, slight upticks in overall temperature, diminishing ice at the polar caps.

Maxim

The previous two types of evidence—examples and signs—call upon what we can see in the world around us. Testimony and authority depend on experts in a community. Maxims and fables, on the other hand, depend upon wisdom in a society. A maxim is a phrase that captures something believed by almost everyone:

- A stitch in time saves nine. (If you do something at the appropriate moment, then you won’t have to work harder later on to fix the problems caused by poor timing.)

- Many eyes make all bugs shallow. (When more people are looking at a project, its problems become much more evident.)

- Revenge is a dish best served cold. (If you want to get back at someone, you should wait until you can calmly plan your revenge.)

- An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. (A little effort to prevent a problem is the same as a lot of effort to fix the problem.)

- It has jumped the shark. (When a story has to resort to ridiculous plot gimmicks to keep the audience interested, its time has passed.)

As the above maxims demonstrate, each specific expression requires cultural knowledge. You won’t know what “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” means unless someone at some time explained it to you. You’re more likely to know the expression if you work in the medical industry, where people regularly repeat it. You won’t know what “It has jumped the shark” means unless you’re familiar with the last seasons of the 1970s sitcom Happy Days, and even then some explanation may be needed. And unless you’re familiar with the open-source movement in software engineering, you won’t understand what is meant by “Many eyes make all bugs shallow.” Because maxims require so much cultural knowledge, older and more experienced people tend to have larger collections of these phrases. Since wise people know maxims, a speaker’s ability to use a maxim appropriately will give the audience a reason to trust them as a wise authority.

To an audience who knows and believes a maxim, the expression can be very convincing. Rather than researching examples of excellent students who study early, I can say: “Instead of cramming for eight hours, you should study thirty minutes a day this week. After all, a stitch in time saves nine.”

Brief Exercise: For a week, keep a notebook and a pen at hand. When you hear an expression that you’ve heard before and that carries resonance with you or someone else, write it down. Then paraphrase the meaning. How often do you use or adhere to maxims in your daily life? How often do you see other people using or adhering to maxims in their everyday lives? In what public discourse do you hear speakers using maxims?

Fable

A fable, like a maxim, captures a bit of cultural wisdom. Maxims package such wisdom in sentences. Fables package it in stories. Consider the well-known fable of the tortoise and the rabbit. The tortoise is slow. The rabbit is fast. The rabbit makes fun of the tortoise and challenges him to a race. The tortoise accepts. During the race, the rabbit runs far ahead and decides that he can take a nap. The tortoise steadily crawls to the finish line and wins the race. What wisdom is captured in this story? There’s the typical maxim: “Slow and steady wins the race.” There’s also another moral: Don’t believe you’re so good that you don’t have to try.

Many fables about mythical talking creatures are attributed to Aesop, of ancient Greece, but some fables come to us as fairy tales, such as those recorded by the brothers Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm (a.k.a. Grimm’s fairy tales). Their story about Hansel and Gretel reminds children not to wander too far or eat too much candy. Some fables are apocryphal stories told about history. George Washington did not chop down a cherry tree when he was a boy, nor did he say to his father, “I cannot tell a lie.” Nevertheless, we tell this fable to remind ourselves that great leaders should be honest. The Dutch who settled Manhattan did not buy the island for a handful of beads. (The Canarsee tribe accepted many gifts in exchange for the land’s temporary use.) But we tell the story to remind ourselves that a profitable real estate transaction often involves a shrewd buyer and an ignorant seller. Finally, fables aren’t restricted to arguments about morality. Astronomers echo a well-known fable every time they call the distance between the Earth and the Sun the “Goldilocks zone.” The moral: The middle—not too hot, not too cold—is the best.

How can a fable serve as evidence? If the audience knows a story and accepts its basic lesson, then the speaker can apply the story’s lesson to a new situation. Even if the audience doesn’t know a fable, however, the story can be very persuasive. Fables get repeated because they are full of drama, intrigue, memorable characters, and delicious plot twists. To convince you that you should study every day instead of cramming, I could tell the story of the three little pigs, which you likely know. I could say that cramming the night before is like building a house out of straw or sticks—trying to make a solid foundation out of minimal effort and shoddy materials. The person who studies every day, on the other hand, builds a house out of brick.

Or I could tell you Aesop’s fable of the ant and the grasshopper:

Every day in the spring, the ant collects a little bit of food and stores it away. The grasshopper sings and dances, eating only what he needs and saving nothing. When winter comes, the ant survives while the grasshopper starves. The moral: To work today is to eat tomorrow. The same lesson applies to studying: To learn everyday is to know tomorrow.

Even if you’ve never heard the fable of the ant and the grasshopper before, you might be convinced by the story because the characters are typical—the creature who plays foolishly and the creature who works diligently. And the results are predictable—playing leads to poverty, and working leads to prosperity. Mentioning that Aesop first told the story centuries ago adds to its persuasive ability. After all, even though he wrote about insects, Aesop was an authority on human morality.

Analyzing Evidence

In what remains of this chapter, we want to offer a basic process for analyzing evidence: First, identify the pieces of evidence; second, relate those pieces of evidence to the reasons or to the principal claim in the argument; third, label the evidence using the terms in this chapter; fourth, analyze the relationships among the evidence, the argument, and the audience. An easy four steps to a good analysis! Perhaps not. It is not always necessary to follow the order that we suggest or to complete all the steps that we outline. And sometimes you may have to go back and repeat one or two of the steps. But the process should at least highlight the things that a careful analysis will accomplish. A careful analysis will show where the evidence is. It will explain how the evidence contributes to the reasons and the claim. It will explain what kind of evidence is in the argument. And it will explain how the evidence relates to the audience.

We also want to point out that, even though we suggest analyzing the reasons first, the evidence may take up the largest part of the argument. Some arguments overflow with evidence, much of it in support of a single reason. As mentioned much earlier in this chapter, if someone wanted to prove that global climate change is really happening, he could point to a litany of signs: rising sea levels, changing weather patterns, increased temperatures, decreased ice at the North and South Poles. Listing all this evidence would take pages, but it would all serve the same reason to believe: Many signs indicate a permanent shift in the world’s climate, so you should believe that global climate change is really happening. Take another hypothetical example. Imagine someone wants to prove that the U.S. electorate is becoming more conservative. They could point to many examples—surveys and interviews with voters—to show that many people hold conservative beliefs. They could point to recent elections won by Republicans—signs that the voters favor conservative candidates. And they could cite political pundits—authorities—who all say that the “silent majority” in America is conservative. This evidence could fill an entire book, even though it would all support the one claim.

Finally, we want to emphasize that evidence, like reasons, is audience-specific. It is easy to imagine evidence—especially certain kinds of evidence—as universally persuasive. Who would doubt statistics from the U.S. census, images from the Hubble telescope, or data from the Large Hadron Collider? Though such evidence may be unassailable, it is not universally convincing, nor is it always necessary. You can tell an audience that there are as many stars in the sky as there are grains of sand on the beach without showing elaborate images of the universe. They will likely believe you without the evidence. And you can tell people that the Large Hadron Collider created a quark-gluon plasma that scientists could use to test for supersymmetry, and the audience will not understand you. (We don’t even understand what that means.) Our point is that different kinds and amounts of evidence are needed for different audiences, depending on what each audience believes, feels, understands, and has experienced. When analyzing evidence, your job is to show the connection to the audience. And the same is true of all rhetorical analysis. Rhetorical analysis explains how a text relates to specific people in a given place at a particular time.

Chapter Assignment

Play Evidence Bingo! In small groups, using the cards below (or cards you make up yourselves), read several articles out loud. Every time someone spots a kind of evidence, shout out its name. If you have a square on your card that lists the name of that kind of evidence, put an X on the square. The first person to have three in a row wins!

Card for Player 1:

| Hypothetical Example | Expert Authority | Sign/omen |

| Testimony | Maxim | Vivid Example |

| Statistics | Sign/indication of fact | Fable |

Card for Player 2:

| Expert Authority | Vivid Example | Testimony |

| Maxim | Real Example | Sign/omen |

| Statistics | Fable | Hypothetical Example |

Card for Player 3:

| Statistics | Testimony | Sign/omen |

| Maxim | Hypothetical Example | Vivid Example |

| Fable | Expert Authority | Sign/indication of fact |

Card for Player 4:

| Real Example | Testimony | Vivid Example |

| Fable | Maxim | Sign /indication of fact/ |

| Sign/omen | Hypothetical Example | Statistics |

Card for Player 5:

| Real Example | Maxim | Statistics |

| Sign/indication of fact | Vivid Example | Testimony |

| Sign/omen | Fable | Hypothetical Example |